The Grammar Move That Clarifies Complexity

There is a quiet power in small, common words, and “and” may be the most underestimated of them all.

Grammatically, “and” is a coordinating conjunction. That sounds technical, but the effect is deeply human: it places two thoughts on equal footing. Not one as the “real” statement and the other as the footnote, not one as the polite preface and the other as the confession. Equal weight. Equal truth.

Here is what makes “and” so powerful: it can hold two ideas, facts, or feelings that seem opposite at first glance, and it refuses to force a choice between them. “And” is where language makes room for complexity.

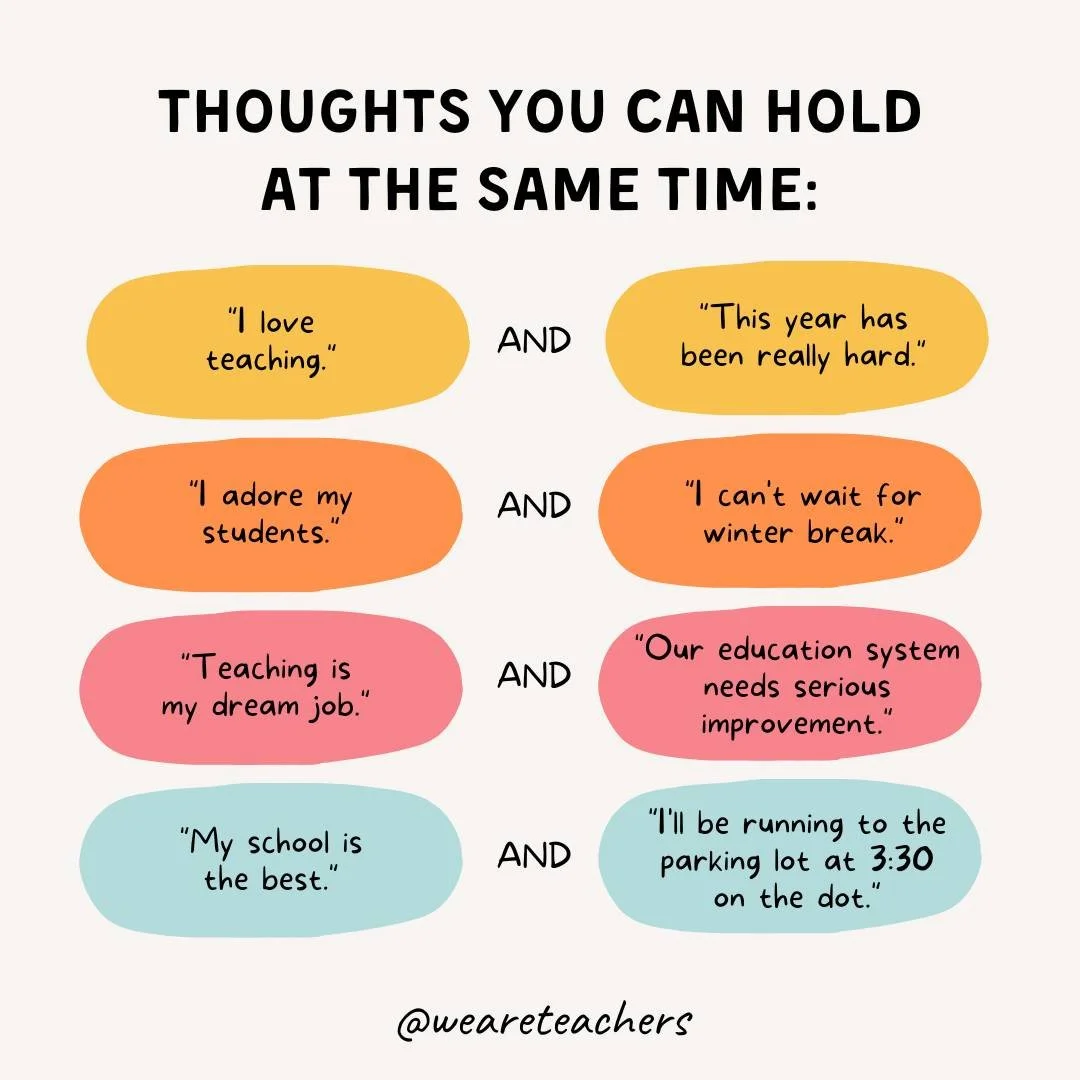

That is why the statements in this post resonate.

The “and” refuses to let either clause cancel the other. If these sentences used “but,” the second half would often read like an eraser: I love teaching, but… (so maybe I don’t, really). “But” is an adversative conjunction; it signals contrast, correction, or exception. It’s useful, and it’s often honest, but it can also subtly train us to rank emotions, to treat one as the official narrative and the other as an inconvenient aside.

Try the swap and feel how the stance changes:

“I love teaching, but this year has been really hard.”

This implies an argument: loving teaching is being challenged by hardship, and one might undermine the other.

“I love teaching, and this year has been really hard.”

This implies wholeness: love and hardship coexist, and neither negates the other.

In the classroom, “and” can be a tiny writing move with outsized impact, especially in reflective writing, narrative voice, and argumentation. It helps writers avoid false binaries. It invites precision. It signals that a writer can carry more than one idea at a time, which is a core mark of mature thinking.

“But” debates.

“And” integrates.

“And” is the grammar of nuance. It holds complexity without forcing a verdict.

From a writing perspective, “and” is the hinge that allows a sentence to carry tension. It creates a kind of emotional parallelism, a balanced structure that says, “Both can be true.” In rhetoric, that coordination produces a tone of steadiness, not a need to explain yourself. The speaker is not defending themselves. They are naming reality.

A few quick ways to apply the “and” stance in writing (and to teach it explicitly):

INFORMATIONAL WRITING: Add precision without forcing an “either/or.”

Move: Use “and” to present two true facts about the same topic, even when they feel like they pull in different directions.

Example: “Volcanoes are destructive, and they also create new land.”

ARGUMENTATIVE WRITING: Make a claim that is strong and nuanced.

Move: Use “and” to maintain a clear position while acknowledging a real trade-off.

Example: “School uniforms can reduce distractions, and they can create equity concerns.”

NARRATIVE WRITING: Juxtapose what a character feels, thinks, and does.

Move: Use “and” to reveal tension inside a moment, instead of smoothing it out.

Examples:

“She smiled at her friends, and her stomach dropped.”

“He wanted to tell the truth, and the lie came out anyway.”

“I ran toward the door, and I wished someone would stop me.”

In a time when so much language pushes us toward extremes, “and” gives writers another option: a sentence that can hold two truths without flinching. That is grammar doing what it’s supposed to do, not just organizing words, but clarifying thought.